Film Review by Marit Östberg

19 December 2018

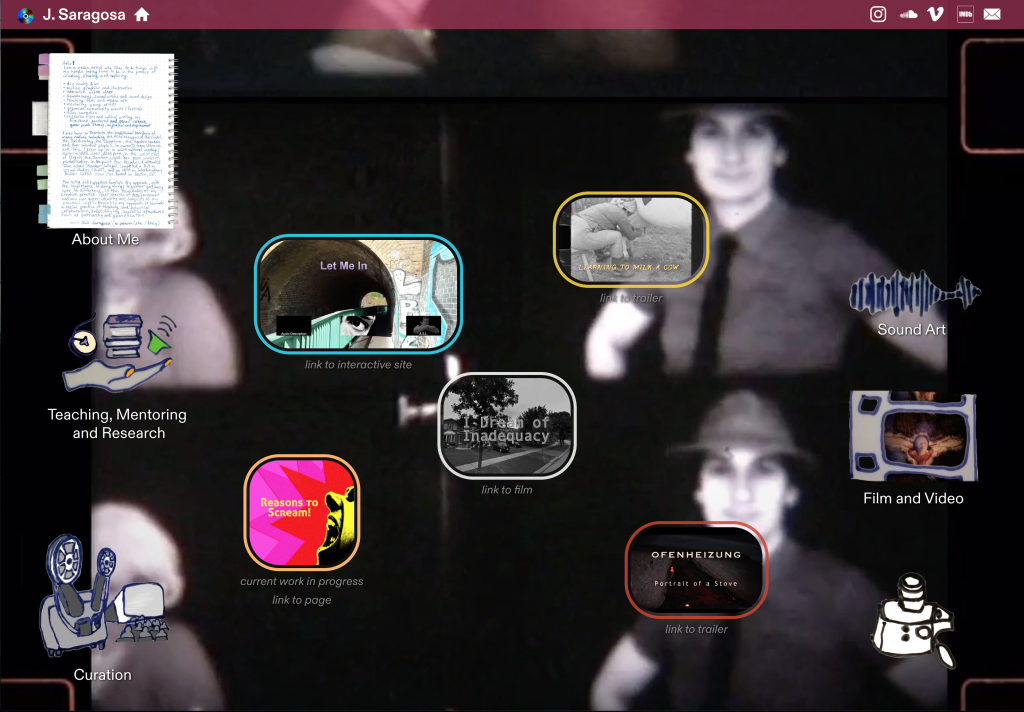

I carry with me one scene that makes me smile from the otherwise pretty heavy narrative of Learning to Milk a Cow. The Canadian filmmaker Juli Saragosa wears a colourful traditional Ukrainian costume. She dances the dance she learned as a child in an inner-city neighbourhood of Toronto. Long colourful ribbons attached to a wreath made of fabric flowers. The ribbons are fluttering in the wind. She looks happy, playful.

There’s a joke about so-called expats in Berlin. We all become DJs, filmmakers or yoga teachers. Juli Saragosa and I moved here around the same time. I became a filmmaker. Saragosa was already one, but started to train to become a yoga teacher just before her arrival. I went to her classes for a while, she helped me breathe in a critical period of my life.

During the years living in Berlin I’ve encountered many expats trying to deal with their histories. They are the “the grandchildren”. They come here to understand something, returning to their grandparents’ point of trauma. Germany. Carrying wounds not really theirs but even so a part of their bodies. Trying to understand. Some of these processes become art or films.

How we inherit our family’s history through our bodies is one of the main themes in Learning to Milk a Cow, even if Saragosa’s voiceover in the beginning of the film states that it is her grandmother’s story she is telling. Grandmother Katherine, more known as Baba to her grandchild, the Ukrainian word for grandmother. Raia was her name before Germany converted her to Christianity. In the year 1943, Raia was nineteen then, German Nazis took her from her family in Ukraine to a Bavarian farm where she lived as a forced labourer until the war ended in 1945.

Juli Saragosa started documenting her grandmother’s stories in 2002 and finished the documentary in 2016. The images have had a long time to take form and be collected from the archives. You can feel this: The poetic voiceover’s intimate and considerate relation to the rich material and fantastic collages interlacing the hundreds of film clips and photos. Both the voiceover and images are accompanied by a carefully chosen soundtrack of mighty Ukrainian choral music.

Saragosa’s voiceover recognizes how her Baba’s story became a part of her during the making of the film, visiting the places where Raia had lived. Saragosa takes us to these places with her Super 8 camera. Through the sentimental damaged Super 8 look she portrays the story that Raia’s recorded voice tells us – how she, together with 23 other girls, was forced on a train to Germany and never saw her family again. Saragosa’s camera captures cows behind fences as the grandmother describes the horrifying train journey to Bavaria. Through the camera lens, and through her own body, Saragosa portrays Raia’s story as a forced labourer. Saragosa puts on a shawl and starts to milk a cow (does the title of the film refer to her grandmother or the grandchild?), Saragosa wears a badge on her chest with the letters “OST” (the Nazis’ badge for the Ukrainian forced labourer), Saragosa feeds the cows and caresses them with such a tenderness as if she wanted to reach through history and make it all good.

There are side stories in Learning to Milk a Cow. The fragmented collages that bind the film together include images from a family album with a mother also digging into history to understand the parents’ traumas. How do we nurture our history? Who is accountable? These issues are never outspoken in the film, but the crucial questions you take with you after watching it. Germany did certainly not pay much mind to Raia’s experiences. She got 1500 Canadian dollars after applying for reparations from the EVZ, an organization that protects German companies from being sued by former forced labourers.

In the second part, the film takes a turn. Saragosa meets up with Angelika, a German researcher and filmmaker creating work about her Bavarian family that used forced labour from the German state during the war. Their paths meet in Berlin when Angelika attends Saragosa’s yoga class. Coming from two sides of Germany’s dark history, dialogues emerge about how forced labour was an essential part of national socialism and that the economic standard in Germany until today is based on these crimes. Together, as if in one voice, they state:

Juli: “They don’t think about that. That the wealth, this middle-class status that they have could’ve come because of…” Angelika: “Exploited.” Juli: “Yes.” Angelika: “And stolen.”

How can the grandchildren come to terms with their histories while facing a future of rising nationalism? Raia never went back to Ukraine after the war. The country was still under Soviet control and the terror of Stalin was no option. The ones trying to return were seen as traitors and sent to Siberia, despite the fact they had been forced to work in Germany. During the same period as Saragosa made her film Putin’s propaganda and hunger for power hits Ukraine. Saragosa draws circles in history, recognizes the past in the present. Raia took her family to Canada and was able to create a good life for her children and grandchildren.

Saragosa notes: “European colonization of Americas enabled my parents to go to Canada where there was prosperity manufactured through exploitation, lies and genocide.”

Saragosa asks her grandmother if she got to say goodbye to her family. Raia answers: “Why do you ask those questions that make me hurt so much?”

How do we carry the history with us while living in a time of nationalism on the rise? First step is to learn how to carry the pain, to breathe. Second step is to take responsibility for what we know, to never let the history be forgotten.

Juli Saragosa’s ribbons flare in the wind when she dances in front of her 8mm camera. They are colourful and unruly.